Bhone Tayza had been impatient to start school. A broken arm had kept the 7-year-old home while the other kids began their lessons, but now that his cast was off, he couldn’t wait to join in.

His mother, Thida Win, was still worried. “Just stay home for today,” she recalls telling her son on his third day back at school last September – but he went anyway.

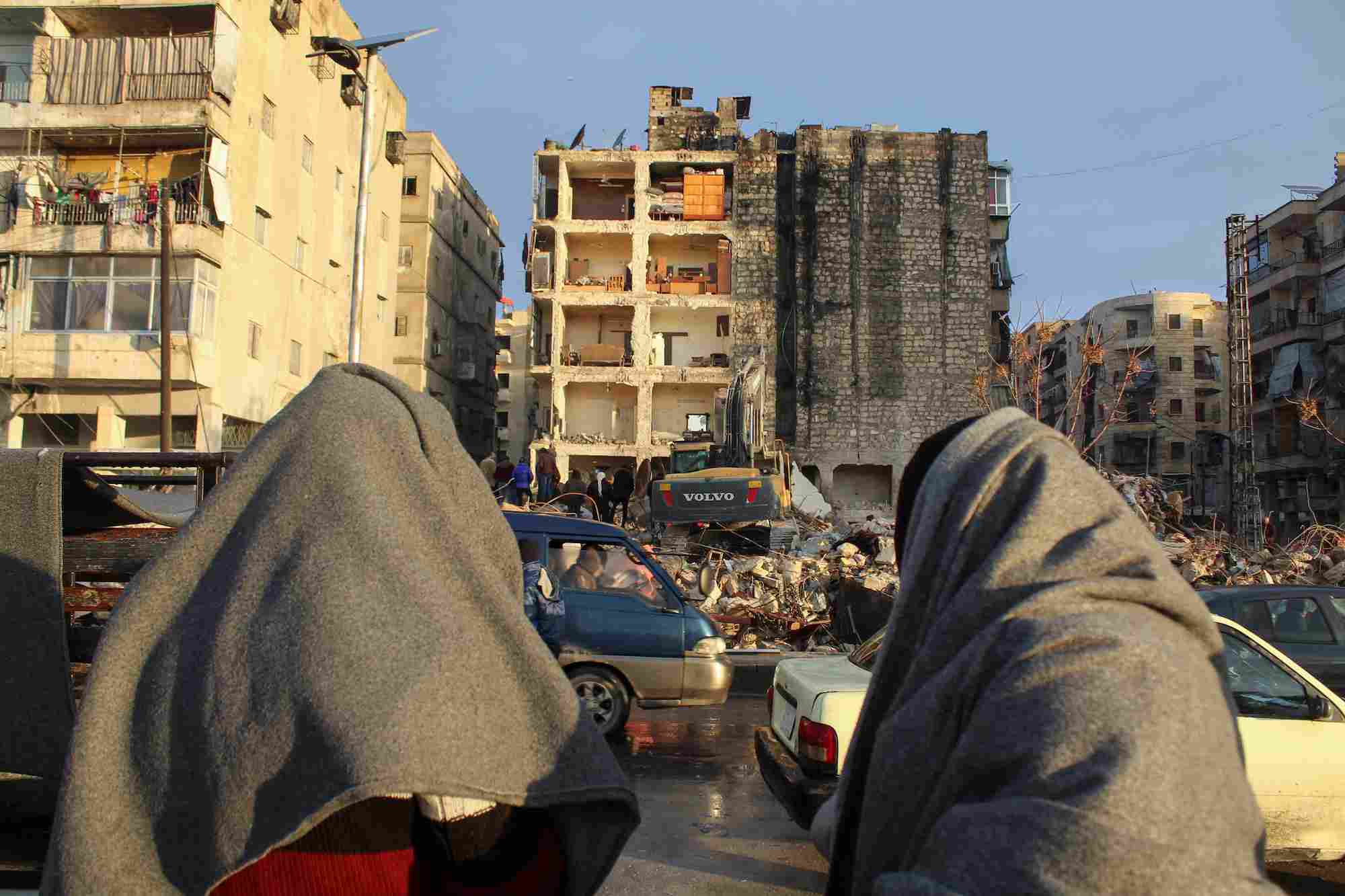

Hours later, the airstrike hit.

Thida Win was home, in the central Sagaing region of Myanmar, when army helicopters began firing “heavy weapons” including machine guns near her house, she said. She took cover until the shooting stopped, then sprinted to the nearby school, frantic. She finally found Bhone in a classroom, barely alive in a pool of blood, next to the bodies of other children.

“He asked me twice, ‘Mom, please just kill me,’” she said. “He was in so much pain.” Surrounded by armed soldiers of Myanmar’s military who had swarmed the school grounds, she pulled Bhone into her lap, praying and doing her best to comfort him until he died.

He was one of at least 13 victims, including seven children, in the September attack – and among the thousands killed nationwide since the military seized power in a coup on February 1, 2021.

The junta ousted democratically elected leader Aung San Suu Kyi, who was later sentenced to 33 years in jail during secretive trials; cracked down on anti-coup protests; arrested journalists and political prisoners; and executed several leading pro-democracy activists, drawing condemnation from the United Nations and rights groups.

Two years on, the Southeast Asian country is being rocked by violence and instability. The economy has collapsed, with shortages of food, fuel and other basic supplies.

Deep in the jungle, rebel groups have taken the fight to the military. Among their number are many teenagers and fresh graduates, whose lives and ambitions have been upended by a war with no end in sight.

They were met with a bloody crackdown that saw civilians shot in the street, abducted in nighttime raids and allegedly tortured in detention.

CNN has reached out to Myanmar’s military for comment. It has previously claimed in state media it is using the “least force” and is complying with “existing law and international norms.”

Since the coup, at least 2,900 people in Myanmar have been killed by junta troops and over 17,500 arrested, the majority of whom are still in detention, according to advocacy group Assistance Association for Political Prisoners (AAPP).

Daw Aye Mar Swe, a teacher at the school, said she ushered students into classrooms as the military helicopters approached, shortly before the horror descended.

The airstrike hit the roof, sending debris falling all around them. The room filled with dark smoke – and then the soldiers arrived.

They began “shooting at the school for an hour nonstop … with the intention to kill us all,” she told CNN.

She shoved her students under beds for cover, but it was of little use. One young girl was shot in the back. As she tried in vain to stem the bleeding, she urged her crying students: “Say a prayer, as only God can save us now.”

When the shooting was over, the soldiers ordered everybody outside, she said. The students huddled together on the school grounds while the soldiers raided the rest of the village and made arrests, said Daw Aye Mar Swe. She recalled seeing Bhone Tayza among the wounded.

The National Unity Government (NUG), Myanmar’s shadow administration of ousted lawmakers, said 20 students and teachers were arrested after the airstrikes.

It’s not clear what happened to them. CNN could not independently verify details of the incident.

organization of armed guerrillas, of using children as “human shields.”

Thida Win and Daw Aye Mar Swe denied these claims. “There is no PDF here, or shooting (done by the PDF),” the teacher said. “(The military) shoot us without any purpose or research.”

For some bereaved parents, the agony of losing their children was compounded by being denied a proper goodbye.

After the strike, two residents, who declined to be identified due to fears for their security, said the military took the bodies away and buried them in another township several miles away.

Thida Win corroborated this account, saying she had cried and begged the soldiers to “let me bury my son on my own … but they took him away.” When she contacted a military commander the next day, he said Bhone had already been cremated. To this day, she has not collected his ashes, saying she would not sign any documents issued by the junta that killed her son.

“There are no words … my heart is broken into pieces,” she said.

Some of these groups effectively control parts of Myanmar out of the junta’s reach – and many are composed of young volunteers who left behind families and friends, for what they say is the future of their nation.

Shan Lay, 20, was a high school senior when the coup took place. Now, he spends his days on the front lines as a member of the MoeBye PDF Rescue Team, a small group of combat medics that treats and evacuates injured PDF fighters in eastern Myanmar.

It can be a dangerous job; Shan Lay recalled one instance when their vehicle was shot at and destroyed by military soldiers, forcing the team to jump from the car and run to safety.

CNN is referring to Shan Lay and Rosalin by their “revolution names,” aliases many in the resistance movement adopt for their safety.

Videos of their daily operations, shared by the rescue team, reveal improvised tools and treacherous conditions. Often, they wear no helmets or protective gear, ducking gunfire in just flip flops, t-shirts, long pants and backpacks.

The clips show the group carrying injured fighters on rocky dirt paths, and providing medical care during bumpy rides on pickup trucks; sometimes they have nothing more than boiled water to sterilize wounds, Rosalin said.

When the fighting lulls, they treat injured civilians displaced from their homes and distribute food.